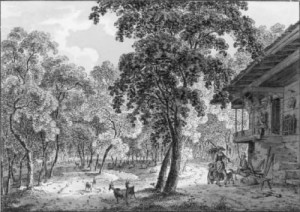

Berglandwirtschaft im Wald

Description

A park-like landscape with majestic trees extends around a farm at Bönigen in the Berner Oberland, a goat herd is dispersed on the terrain, a farmer has collected leaves with a rake and is carrying in a basket to a staböe: The coloured drawing from 1808 displays a typical image of agriculture at that time in the mountain regions,

where forests are important not just as a source of wood. It also served as a pasture to obtain hay, for agriculture and obtainment of fruits. Also as a source for needles and leaves, bedding for the stable and filler for mattresses. In the two preceding centuries, an agrarian Revolution had taken place: Maize and potatoes replaced the widespread farming and in the lowlands milk production became widespread among Farmers. Even cheese, an important export product in the mountains, was increasingly produced in the lowlands. The mountain regions suffered from the economic consequences and were further subject to strong pressure from the forest industry, which thought completely different of "good Woods" than in the previous centuries. It was spoken of "plundered Woods", which was being destroyed by land use. At its root this was an use conflict with a social component aggravated by the economic crisis taking place in the mountainous regions, which hitherto had relied strongly on milk-making. The introduction of potatoes and maize had dusplaced agriculture. Straw, necessary for animal-keeping in stables, became a rarity. Aside from reeds and swamps (mowed in autumn) the only replacement was in forests. Fast population growth and the impoverishment of large parts thereof led to emigration and for those which had stayed behind a life hanging on a thread: The use of forests was a necessity for survival. Contemporary accounts discuss "cleaned-out" forests, in the Berner Oberland supposedly beech leaves were collected so carefully that "one can count the leftover leaves" according to a forestry report in 1874.

The "forest strew", which includes not only leaves but also needles, ferns, mosses, grass and earth, in many parts of the Alps was far more important economically than wood. That included the cutting of low-elevation branches. It was not simply a matter of bedding for stables but also food for animals, mainly goats, which were considred Poor Man's Cows. The milk from two goats could feed a family of five without land. In summer the animals fed in forests and in winter they were nourished with leaves, needles, moss and lichens. Conflicts with forestry arose, which considered humans as "forest pests" which "through pasture and collection of strewn material" damaged the forests, as was still claimed in the 1939 Handbuc der Schweizerischen Volkswirtschaft.

Already decades earlier, legal restrictions had been imposed on this kind of forest use. Flood disasters in the valleys had been blamed on the use of mountain forests, but the economic situation prevented the enforcement of the rules. The conflict was eventually resolved by better traffic access to the mountain regions, the start of tourism, new economic activities and large subsidies for montane agriculture. The semi-open species rich forests of that time, the lack of a clear delimitation between forests, meadows and fields are history and are maintained by the chainsaw when needed for environmental reasons, such as keeping aurochses. The "good hood" has shown itself as adaptable.